How the government spends its money in Malaysia normally comes into the public eye during the yearly Budget announcement, when year-on-year comparisons can be made. But what about longer term trends?

Government expenditure forms an additive component of gross domestic product (GDP), the indicator used to assess a country’s growth and general (though disputable) economic wellbeing. Like individuals equipped with credit cards or credit facilities, how much the government spends in any one year need not be limited by the amount it will earn in that year, as long as it can repay its debt. This means that the figure for government spending can increase even in times of crisis when funds are low.

Conventional economic wisdom suggests that government expenditure should rise in times of economic crisis, as higher unemployment requires greater welfare spending to help cushion the fall. A country with well-implemented automatic stabilisers, as taxes and welfare benefits are called, will experience countercyclical fiscal policy: in good times, government spending should fall, and vice versa for bad times.

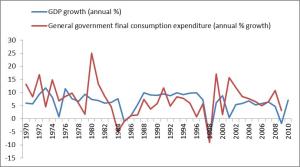

The story for Malaysia, however, appears to be the complete opposite. Government spending (the red line) closely tracks GDP growth, falling when there is a recession and rising in good times. In other words, we spend too much when times are good and are then forced to cut back when revenues fall. While causality can run both ways (that is, fiscal policy affecting GDP growth instead of the other way round), numerous papers have suggested that fiscal procyclicality is a real political economy problem, one that we should be wary about.

There is a general tendency for budgets to be structured as expansionary ‘election budgets’ with something for everyone, especially when times are good, but lessons should be drawn from the experiences of Japan (the lost decade) and the more recent credit crunch, where fiscal stimulus eventually became key to bringing countries out of recession and/or stagnation. Instead of finding the best way to fix a problem in the economy, we do not want to be caught in the trap of making the magnitude of a recession even worse.

——–

My Pick of the Week –Quotable Quotes:

“Markets are the essence of a market economy in the same sense that lemons are the essence of lemonade. Pure lemon juice is barely drinkable. To make good lemonade, you need to mix it with water and sugar. Of course, if you put too much water in the mix, you ruin the lemonade, just as too much government meddling can make markets dysfunctional. The trick is not to discard the water and the sugar, but to get the proportions right.” – Dani Rodrik

, the graph shows General government final consumption expenditure. Does this include investment expenditure? I know certain data don’t differentiate between those 2, but just to check.

Hi Jia Cheng,

Thanks for your question! All data was obtained from the World Bank Database, but I believe that general government final consumption expenditure, with the word ‘consumption’ in it as such should not and most likely does not include investment expenditure.

In the standard national income equation of Y = C+I+(G-T)+(X-M) , this should represent G.

Wikipedia corroborates this:

“Government final consumption expenditure (GFCE) is a transaction of the national account’s use of income account representing government expenditure on goods and services that are used for the direct satisfaction of individual needs (individual consumption) or collective needs of members of the community (collective consumption).”

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Government_final_consumption_expenditure

If it did include investment, then there could be some merit in procyclical spending (in the sense that investment expenditure during good times would be beneficial in the long run, including times of future crisis). As it stands, though, I doubt that is the case.

I’m sorry I wasn’t being clear, but I was refering to government Investment expenditure before this, and I think you still managed to understand me somehow. Pointing this out to not accidentally confuse anyone ( most people would just recognise my mistake), but yeah, I’m sorry.

Here are my thoughts,

1. Your national income equation looks weird to me. The one I normally use would be Y=C+I+G+(X-M)

There’s no Taxation, T in my equation. If you were to include T, something similar to transfer payment, won’t that be double-counting? I’m also aware that this is only an identity, it holds true because of the way we define it. Hence, different interpretation results in different equation. But the basic idea should be the same.

2. And if you’re focusing on how government spending can be used to offset short-run fluctuation, I assume you’re relying on Keynesian logic here. And, following this logic, it doesn’t matter where spending comes from, either government final consumption expenditure, government investment expenditure, or even to give away money like Santa. Therefore, isn’t it better to have data on Government spending as a whole, instead of having just the consumption part?

I quote wikipedia,

Government acquisition of goods and services for current use to directly satisfy individual or collective needs of the members of the community is classed as government final consumption expenditure. Government acquisition of goods and services intended to create future benefits, such as infrastructure investment or research spending, is classed as government investment (gross fixed capital formation), which usually is the largest part of the government gross capital formation.

What I believe is, government spending as a whole, increases no matter what in recent times, explaining the persistent inflation in our economy. I come to this belief after accounting for the stimulus plan we had due to the recession. This is just my guess and I can’t seem to get any data on government spending as a whole. Even statistics.gov.my is not helpful here.

The best closely related data I have is on gross government debt. And readers should note that it’s closely related but definitely not identical. I don’t want to confuse anyone.

http://www.indexmundi.com/malaysia/public_debt.html

From 1998 onwards, our debt seems to have nowhere to go, but up. The same thing PROBABLY happened to government spending as well. Just PROBABLY.

My conclusion is actually not far from yours. I agree completely that fiscal procyclicality is a problem. It’s just that in Malaysia, (I assume) we spend a lot in good and bad times.

Jia Cheng,

Whoops. Lesson learnt: never respond to stuff while in the office and multitasking.

1. You are entirely right on the income equation point. The equation Y=C+G+I+(X-M), when rewritten, will yield the savings identity (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Savings_identity). In essence, public savings is simply tax revenue less government expenditure (T-G), i.e. whatever that is not spent is saved.My humble apologies for the confusion (I mixed up the two) and I stand corrected.

2. Allow me to direct you to this piece from the Malaysian Institute of Economic Research, which also supports my views, which I left out because this is an EconSmart article – I try to be accessible – and also because I intended to try and do my own research on the subject before coming to a conclusion (sadly, I am not yet a practicing economist and hence do not have as much resources as others would).

Click to access DrSohrab.pdf

Several points emerge from this:

a) fiscal procyclicality is there and is clear since the Asian financial crisis

b) investment spending has a more permanent impact than consumption spending, which would not be that damaging should investment spending on its own be procyclical).

c) this is not the case – investment spending (developmental expenditure) is low, whilst government consumption is steadily increasing, and highly correlated with economic growth.

On aggregate, this means that as a whole, fiscal procyclicality is still occuring, and that there is still more spending in good times overall than in bad.

Addendums:

On point b) , I should probably mention that it is in fact a more permanent positive impact, not a negative one.

Additional points you’ve raised that I’ll briefly note while I’m at it:

i) You suggest that higher government expenditure leads to higher inflation, but I think it is important to bear in mind that inflation is also a result of many other things independent of fiscal policy. Higher consumer spending, an asset price bubble, higher import prices, and exchange rates all affect inflation. Personally, I believe our inflation problem is a combination of all these, as well as the redirection of foreign investment from Europe to Asia, owing to the crisis, which in turn stimulates the domestic economy.

ii) Similarly, an increase in debt does not come from government spending increases alone. A significant portion of debt may be foreign-denominated debt, and depending on currency fluctuations, the nominal value of debt may increase or decrease.

Also, I may be wrong but I seem to sense a certain wariness on your part on ever-increasing govt debt. Not a bad thing, especially given the Euro crisis currently, but please allow me to point you to this: http://econsmalaysia.blogspot.com/p/faq-on-malaysian-government-debt.html

I agree with you that government debt should not be confused with government spending, especially in the context of this article. Procyclical government spending is not desirable because it might limit the ability of governments to use fiscal tools when they are actually needed, and when they matter the most.

I’ve skimmed through the presentation. Most of it are beyond me but slide 5 from his presentation shows increasing fiscal procyclicality very clearly. However, it should be noted that, the correlation coefficient ranges from 0.25-075 or 0.5 ± 0.25 at its peak. These values are definitely not close to 1. It shows increasing fiscal procyclicality but not necessarily high fiscal procyclicality ( relative values compared to other countries needed, my guess here). The question still boils down to the downside of fiscal procyclicality. But given such data, I think the government still has sufficient time to adapt to a better fiscal position. It is not like our fiscal procyclicality is at 0.8±0.1 or something like that. And, articles like this, which points out the downside of fiscal procyclicality is a very good start!

Jia Cheng,

I think you’re conflating two different issues here – the existence of fiscal procyclicality versus countercyclicality, which is at the heart of this article, and high fiscal procyclicality versus low fiscal procyclicality, which admittedly will involve a host of other economic considerations. The point I’m trying to make is that – fiscal procyclicality exists, and is bad. That really is it, and I think the case has been proven from our previous comments. 🙂 Going deeper will probably yield more questions as you have alluded towards; perhaps you’d like to take up the hat and write about that?

My gut instinct is that, obviously, high procyclicality is worse than low correlation figures, but the fact that we cut back on spending in bad times is indicative of something needing to be corrected.

On your response to nk23, correct me if I’m wrong but your response suggests you’ve slightly missed the point he’s making. DEVEX is -not- planned according to economic cycles; that is, it is acyclically determined, given its long term 5-year plans. As such, it cannot be associated with any attempt to see a correlation between cycles and spending as it is largely independently determined because of the nature of the government’s decisions.

As procyclicality as in my article refers to analysing the Government’s response to economic cycles (and note that all academic papers analysing this will also attempt to confirm causality running from cycles to fiscal response), OPEX is a fair indicator of fiscal response.

Hi Jia Cheng,

The data you’re looking for can be found here:- http://www.epu.gov.my/publicsector

Also, there is a subtle difference in the equations

Y = C + I + G + NX (Net exports)

and

Y = C + I + (T-G) + NX

For one, fiscal policy is not just government spending. It could be a change in government revenue, proxied by ‘T’. The fiscal multipliers for T and G are different.

Also, there is a difference between consumption expenditure and investment expenditure. While it may seem that it is a dollar-for-dollar sort of thing, the multiplier effects of consumption expenditure and investment expenditure are also different. But anyway, that’s a bit straying from the point.

The reason for using consumption expenditure, especially in Malaysia, is because the government’s consumption/operational expenditure (OPEX) is determined on a year-to-year basis through the Annual Budget. The investment/development expenditure (DEVEX) is determined based on the 5-year Plans produced by the government (which are now 2-year rolling plans). So, to really see the cycles of spending, it would have to be seen through the more ‘discretionary’ spending which is generally OPEX in Malaysia. If you were to include the DEVEX which was planned for 5 years at a time up till 2011, it does not necessarily reflect the ‘cyclicality’ of spending. Since OPEX is determined on an annual basis, it works better as a basis of spending cycles.

nk23,

Actually, that was my inital point,

Why would you want to show fiscal procyclicality using only OPEX? If as you’ve said,

So, to really see the cycles of spending, it would have to be seen through the more ‘discretionary’ spending which is generally OPEX in Malaysia. If you were to include the DEVEX which was planned for 5 years at a time up till 2011, it does not necessarily reflect the ‘cyclicality’ of spending. Since OPEX is determined on an annual basis, it works better as a basis of spending cycles.

OPEX is generally more cyclical than DEVEX, Then, including only OPEX and excluding DEVEX, you’re magnifying the cyclicality.

overestimating instead of magnifying would be a better word choice. Sorry!

Hey Michelle!

Just a thought, maybe, just MAYBE, this just shows how dependent our economy is on gov projects, if u know what i mean 😉 (highlighting that G affects gdp)

And usually when there’s an econ crisis, Msia doesnt get hit as hard as other nations rite? (assumption) so the bad times ain’t that bad, in relatively to others.

Hi Jesh! Thanks for dropping in!

I’m not sure since I haven’t looked at it properly, but I think the general consensus is that Malaysia is primarily domestic-demand driven. Not too sure which component affects it more heavily – government or consumer, but I’m guessing G is quite significant as well. Perhaps something to look at in further articles 🙂

On the impact of econ crises, it depends on the extent to which we are exposed to it. If it’s a domestic crisis, I have a feeling we will be severely impacted . If it is a global scale one, such as the Eurozone crisis, the impact depends on how much of our export demand is linked to the affected countries, and how much our financial system et al. is prone to contagion effects. So, say, a bank run in Greece will hurt Spain banks if their banks lend heavily to Greek banks (interbank lending) and so on.

Generally, I think, the need to cushion/prepare for such problems should still be something the Government keeps in mind. 🙂